Let’s make some connections

I’m watching the @dbsthinktank and was reminded of an important point about how the brain’s meat-space relates to the output behavior space.

Namely, neuroscience has this implicit assumption that a single symptom must have a shared problematic region. This is trivially easy to show wrong - I’ll do that here.

Circuits and Flows

I tend to not like the use of the term circuit when referring to brain networks 1. But, here, we’ll talk about an idealized circuit in the brainspace and how it relates to a symptom in the mindspace 2.

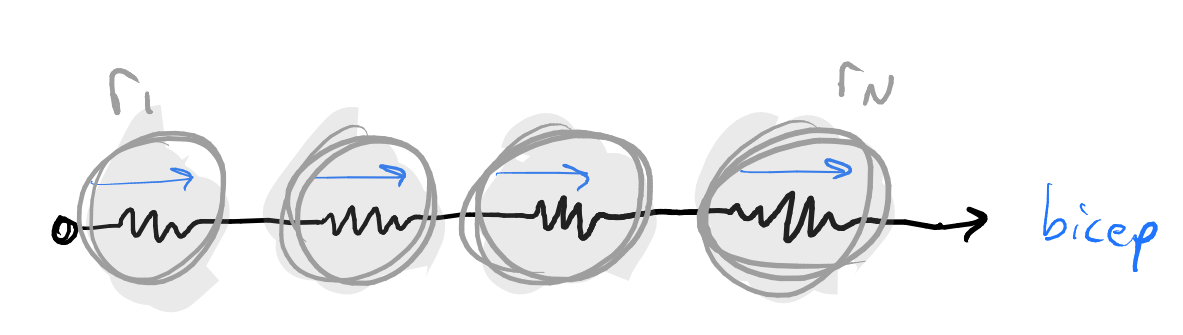

Let’s build a simple circuit where each resistor is a different region, but they all flow into the same end-behavior.

Knowing what we know about circuits, a break in any of the resistors of this circuit will lead to a loss of current flow, and a loss in the end function = behavior.

Common Region is Not Necessary for A Symptom

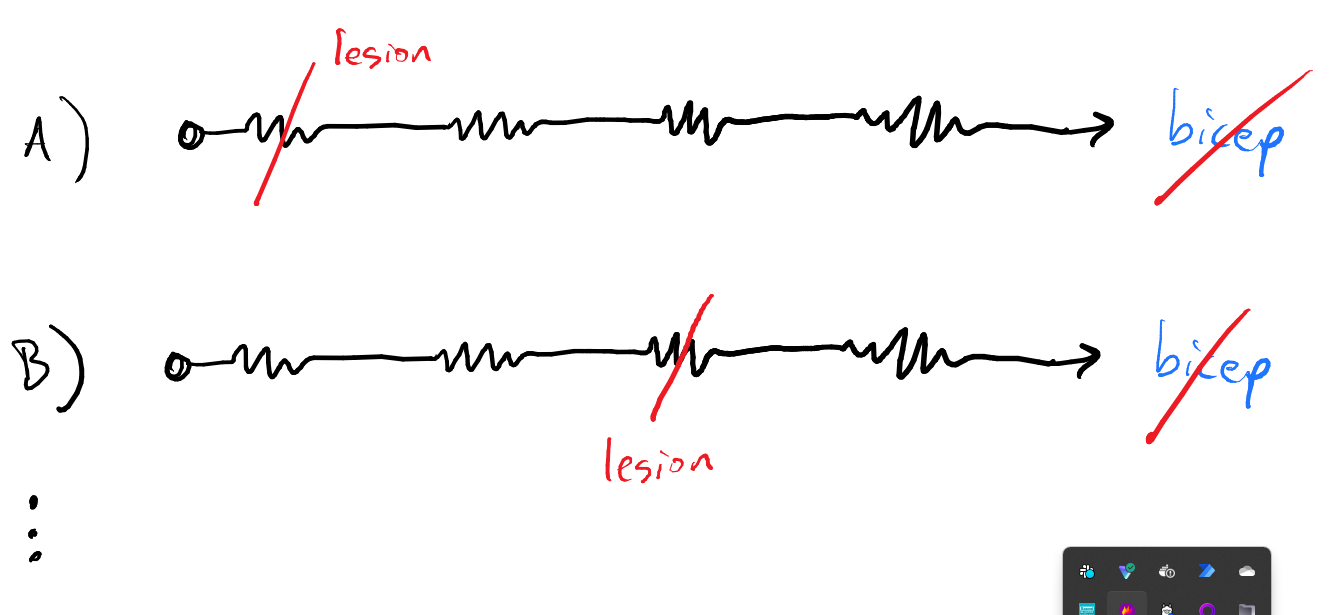

Right off the bat, we see that the same loss of function can arise degenerately from “lesions” in one of any of the resisters.

If we’re obsessed with finding a “region $\leftrightarrow$ symptom” mapping then we’ll spend decades arguing about which one-lesion most happens and/or explains the symptom. It’s clearly, at least here, “circuit $\leftrightarrow$ symptom”.

More on this (and how parallel circuits build in robustness that is relevant to neuro/mind stuff) soon!

Too often, people call something a circuit when they really just mean a physical loop. What makes a circuit more than a loop is a conservation law on a flow that happens on the loop. ↩︎

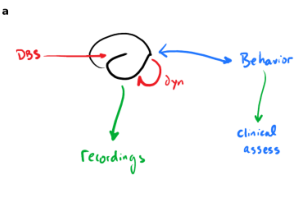

This is a conversation for later, but I’ll outline the difference between the brainspace and mindspace elsewhere (figure from my dissertation).

In brief: we should assume they’re separate layers and wait for data to tell us they’re actually identical. It’s unlikely that they’re identical though because whatever makes us think the neurons int he brain relate to “mind” would apply to the neurons in the spine. And there’s no compelling a priori reason why activity in spine neurons can affect the mind in the same way as brain neurons - some of which extend into the spine.* ↩︎

In brief: we should assume they’re separate layers and wait for data to tell us they’re actually identical. It’s unlikely that they’re identical though because whatever makes us think the neurons int he brain relate to “mind” would apply to the neurons in the spine. And there’s no compelling a priori reason why activity in spine neurons can affect the mind in the same way as brain neurons - some of which extend into the spine.* ↩︎