Two Wrongs Into a Right

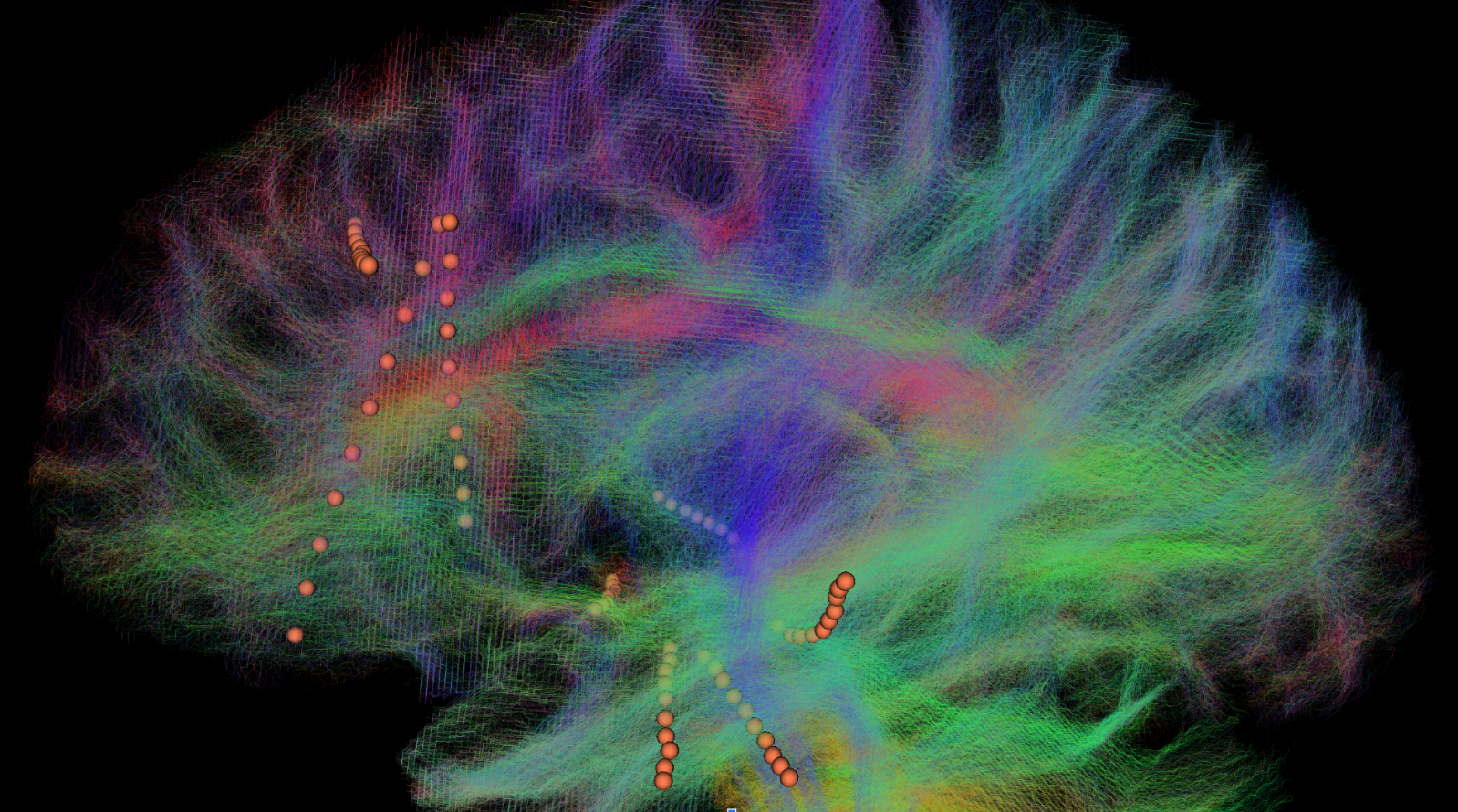

Just had a conversation with a friend whose startup I’m advising for and I was telling him about my current postdoc project. In a nutshell, I’m helping develop a next-generation wiring diagram of the brain - but I’m also making sure it’s clinically relevant.

A new wiring diagram with electrodes embedded…

Much more detail on that later (along with pubs) but for now what I want to talk about is a simple observation (unproven).

Averaging Trajectories is Bad

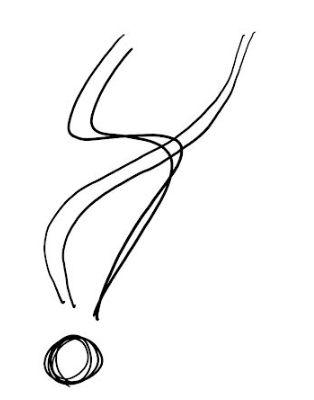

Imagine we’ve got four distinct streamlines (axons or white matter tracts) in four distinct patients, but they’re all streamlines associated with a specific symptom. Our goal may be to map out which streamlines are associated with which disorders/syndromes1.

Four Streamlines from Four Patients - obvious stereotyping here leads to a “bimodality”

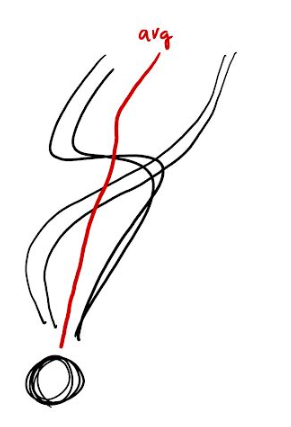

One of the mainstays of science is averaging - usually with the mean. In oversimplification, the mean is just kind of “the middle” of everything involved. So if we take the mean of the four whatevers above, we’ll see

The “mean” streamline is somewhere in the geometric middle… mostly where there is never a streamline component in any of these patients.

The problem? That mean is almost-everywhere explicitly not where any of the original lines were. So, if this was a neurosurgery and we were trying to hit one of those four streamlines in an individual patient, then aiming for the mean would almost-certainly not hit anything. The mean is a ghost of sorts, an analytical trick that doesn’t reflect much of anything about the things we actually care about.

Error in Implanting Helps

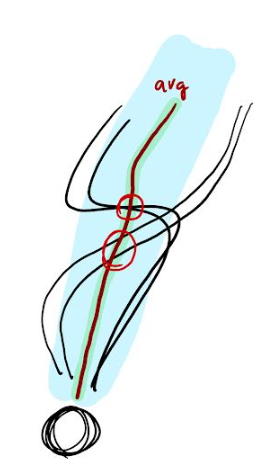

If you’re a proud neurosurgeon that zealously hits exactly the coordinate given to you then you’ll spend an extreme amount of energy and time hitting the precise coordinate given to you. But if that coordinate is an average from individual streamlines, and those streamlines have some form of multimodality, then your proud neurosurgeon is hitting vapor.

Two surgeons of different skills - green is very precise and zealous while blue is much less precise. The red circles are where green actually overlaps with a real streamline.

Imagine a different neurosurgeon, one that isn’t as precise in implanting the electrode. They have a bigger error, so when you give them a coordinate, the actual spot they implant in will be further away from that coordinate than our zealous neurosurgeon.

But, wait a second… that means that “different” neurosurgeon is actually more likely to implant in a way that hits the real streamlines in each of the patients.

We actually see a case here where errors can cancel each other out! 2

I’m a big fan of “loosen up” in science because I think the bean-count types have a very negative impact on the serendipity critical for good science. This is just one example of where being overly pedantic can actually hurt our ability to get things done IRL.

My current work is indeed extending the work done in Hollunder 2024). ↩︎

This isn’t a new concept in engineering - the idea that jitter can come in and actually help makes perfect sense. A sort of “stochastic” regularizer that can help us cancel out the inbuilt error in what’s given to us. See things like vibrational control and dithering. ↩︎